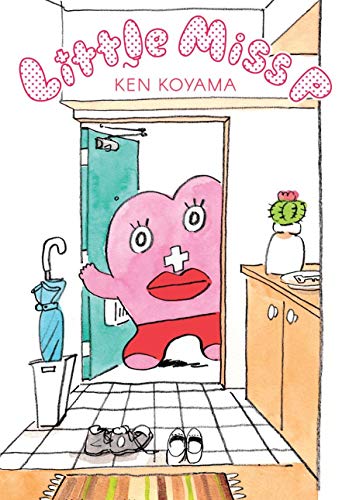

By Ken Koyama. Released in Japan as “Seiri-chan” by Enterbrain. Released in North America by Yen Press. Translated by Taylor Engel.

I will admit that of all the surprising licenses that I saw Yen announce at Anime NYC, this was probably the most surprising. Mr. Men and Little Miss have been around forever, and I have seen pastiches of them before (see the Doctor Who series that came out recently). And Japan has anthropomorphized seemingly everything, from battleships to countries. So the concept should not be that startling, but somehow the idea of a giant period wandering around punching women when it’s that time of the month still made me blink. But, having finished this volume (complete in one, I believe), it’s actually handled pretty well. While there’s humor involved, the humor is more subdued than I expected, and Little Miss P tends to be a lot more sympathetic than you’d expect given that they’re punching women all the tie and taking their blood. It’s a manga that’s trying to show off what happens to women every month, how it can vary from person to person, and how to cope with it.

The book is divided into chapters, each one dealing with a different woman and their encounters with Little Miss P, a walking, talking period. Little Miss P shows up when it’s that time of the month, punches them in the uterus, draws their blood with a giant syringe, and then usually stays around to chat now that the woman in each chapter is feeling miserable. We see a housewife who’s been trying to get pregnant, a convenience store clerk with low self-esteem, two magical girls (one of the more bizarre chapters, but it does show off how different women can have different types of periods), etc. We go back to the Edo Period, when menstruating women had to go sleep in a shed apart from their home; meet two high school drama geeks who bodyswap so each can see how the other half lives; and watch a woman in a new relationship try to bond with the man’s young daughter, who’s just gotten her first period.

The best story is probably the last one, which shows a “fictionalized” version of how Japan first brought out disposable sanitary napkins, showing the woman behind it fighting against men who don’t want to fund it because it’s not something they care about. There’s a lot of analysis of how the marketing was handled, and how careful everyone had to be to make it accessible but not offensive. It was really good. On the downside, while I was entertained by Little Miss P, and certainly the use of the character made this more marketable than simply “a short story collection about various women and their periods” would have been, sometimes it was a bit annoying. And adding the male versions, with Mr. Libido and Mr. Virginity, fell completely flat for me, with the exception of the bodyswap chapter, where it actually worked in context.

I wouldn’t pick this up for the concept – a little Little Miss P goes a long way. But for a series of short stories about women dealing with that time of the month, it was very readable.