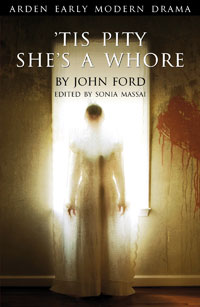

By John Ford. First published in 1633 (approximately 7-8 years after its first performance) by Nicholas Oakes for Richard Collins. Current edition published by Arden Shakespeare in 2011.

Sometimes I think that the current generation on the internet likes to believe that they were the ones who made incest cool, what with all the squee and the Ouran and Harry Potter fanfics out there. But incest has been around since pretty much the dawn of mankind, and has been written about in the greatest works of literature just as much. Almost every high schooler has to read Oedipus Rex these days, though I suspect their local church likely skips over all the Old Testament fooling around.

Thus, in terms of being a play about incest, John Ford was not breaking exciting new ground. The new ground was in how he dealt with it. This is not the usual wacky comedy uncle lusting after his sweet young niece as we’ve seen in other Jacobean plays, nor are the siblings royalty (incest is always more acceptable when they’re kings, strangely enough). No, we have a merchant family here, and their son, Giovanni, is no slavering neanderthal. Not for him the baseless lust approach. He is madly in love with his sister and so he tries to rationalize it intellectually, coming up with all sorts of arguments he can present to his local friar. The friar’s position can basically be summed up by this ellipsis: “…” Luckily for Giovanni, his sister Annabella has fallen madly for him as well, and they declare, then consummate their love in Act II.

The next three acts are everything going to hell, as you can imagine. This is a tragedy, and there will not be door slamming and talk of sardines here. A lot of modern productions of this play apparently want to focus purely on the main couple, and cut out a lot of the other stuff going on, which mostly involves Annabella’s many suitors and a whole lot of plotting of revenge. Which is a shame, as it helps to show that, despite what many critics have said over the years (usually in the process of condemning the play), Ford is *not* sympathizing with the leads. He does not regard their love as Romeo and Juliet, and the way the production plays out shows this. He does not, however, portray either Giovanni or Annabella as monsters. This is the difference.

Annabella actually shows remorse for her mistakes of passion, right about when she realizes that her troublesome suitor, Soranzo, actually does love her. She is also not the instigator of the relationship (which makes it harder to blame the evil woman seducing the poor innocent man, a common enough reasoning in this time period), and ends up having her heart gouged out of her by a now insane Giovanni. Nevertheless, while the play was very popular at the time it was first written and performed, it was condemned by critics for years afterwards, with the compilers of Ford’s Complete Works choosing to omit the play entirely rather than sully the book with this heathenism. It also was thought unsuitable for the stage and unperformed for about 250 years, only being revived consistently after 1940 or so.

This is not exactly a fun play to read, but I think it’s very well-written. And, as with Shakespeare, I think it’s a lot more ambiguous than usually ends up being presented on the stage in modern productions. Ford is not saying the incestuous lovers are right, but he is saying that they are human, and that we can understand their all too human failings. Thus the title, which aptly sums up those two dichotomies: ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore.