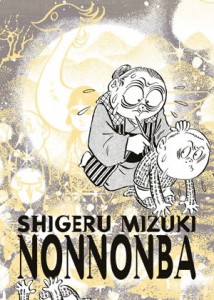

By Shigeru Mizuki. Released in Japan as “Nonnonba to Ore” by Chikuma Shobo. Released in North America by Drawn & Quarterly.

It feels somewhat odd that after reading Nonnonba, a semi-autobiographic epic by the creator of Gegege no Kitaro, the man who is known worldwide for his amazing yokai tales and characterizations, that I found the yokai in it the least engaging part. Oh, don’t get me wrong, there are some spectacular spooks here. My favorite was probably Azuki-Haraki, who looks as if he had been drawn by guest artist Robert Crumb. But though there are yokai and supernatural elements throughout, the reason this is such a famous title – it’s gotten many accolades ever since its first publication in 1977 – has been its human characters, in particular Shigeru himself.

There are several main plotlines that flit through Shigeru’s life as he grows older in this volume. His flighty father’s continued schemes to chase his dream – and unemployment that inevitably follows. The young child gangs that roam the streets, which seem to be undecided as to how serious they are – especially after their new leader has Shigeru ostracized. His grandmother – the titular Nonnonba – moves back in with them after the death of her husband and is very much what you’d expect, dispensing good advice, acting as a nanny/doctor, and occasionally dealing out exposition on yokai.

One of the main things I noticed, though, was the series of girls approximately Shigeru’s age who arrive, seeming to be potential love interests, and then move on. At first this is sudden – “Oh, she died of the measles a week ago”, and you accept it as part of what being a child in 1930s Japan was like. Then we meet a sickly girl who enjoys Shigeru’s drawings, and given she has ‘doomed’ written all over her (if this were a Western comic she’d be dying of consumption), one can briefly raise an eyebrow. Then, in the last third of the book, we meet Miu, a young girl who is part of a ‘family’ moving into a haunted house – and can also sense nature and the supernatural in an almost psychic way. I was fairly sure she would die as well – the color pages at the start made me think they were all going to the land of the dead – but her fate is far more realistic, fitting in with the darker tone of the 2nd half of the book.

Still, the book itself is not depressing. Life is something that has to be accepted, in all its facets. Mizuki is an expert at capturing his childhood in a way unfettered by preciousness or overanalysis. There’s also a bit of eerie prescience here – Shigeru reforming the teen gangs to ‘pacifism’ is all very well and good, but I kept being reminded that this group of kids would be going off to war in a scant few years. This is probably why Shigeru the child has an emphasis on pacifism – and why the ostracized gang eventually joins him over the dictatorial leadership of the stronger Kappa (Kappa being a nickname, he’s not a yokai).

I wasn’t as blown away by this as I thought I would be – Gegege no Kitaro remains the title I want to see here the most – but it was a nice, solid autobiography, mixing reality and fantasy in such a way that each complements the other. There’s a lot of extremely flawed human beings here, including Shigeru, but the overall mood is one of nostalgia and remembrance.